I’m going to show you some numbers.

| Industry standards | Prices | Company/writer |

|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs 60th Anniversary Book | SG$198,750 | Nutgraf |

| National Library Board Coffee Table Book on LAB25 Project | $35,000 | Hong Xinyi, Writer |

| Canberra Primary School Coffee Table Book | $12,650 | Chung Printing |

| Memoir | $10,000 | John Lim |

But don’t fall off your chair.

In 2025, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs hired Nutgraf to write their 60th Anniversary Book.

It was a cool $198k.

You might think it’s an anomaly, but just look at what the National Library Board of Singapore paid for writing, interviewing and research services for their coffee table book.

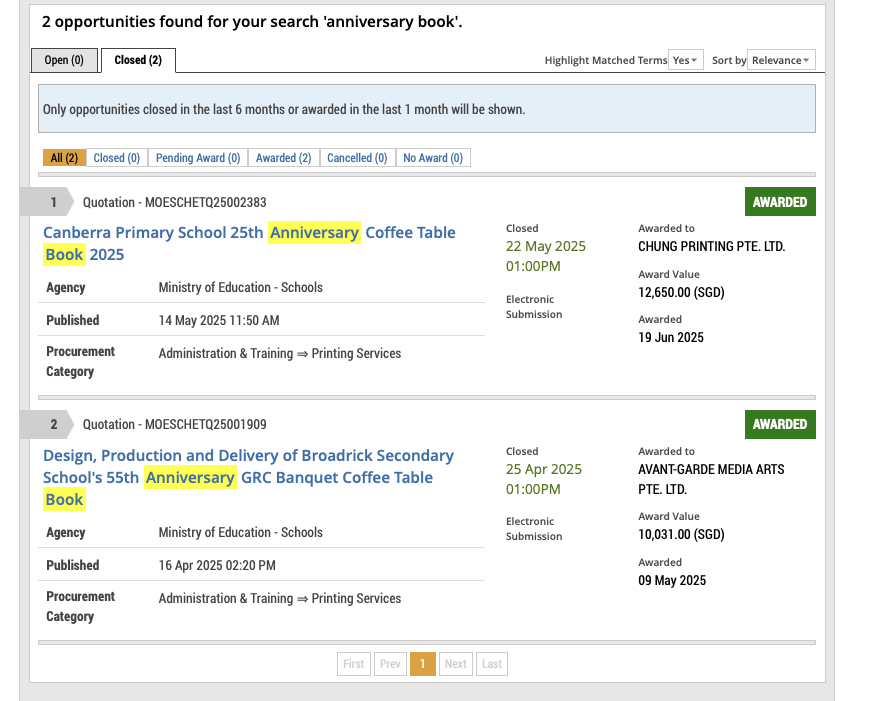

Of course, these are Singapore’s government agencies, and they have bigger working budgets.

But if you see smaller schools, you also see a five-figure sum.

But if you’re someone in the private sector, how much should you be paying for such work?

In July 2023, the CEO of a shipping company with 20 offices around different parts of Asia approached us to do his memoir. We charged him $10,000.

But of course, before we tell you what we did, the deeper question to ask is,

is it worth paying for?

What’s the point of paying so much money for a book?

Do people even read books?

You’re paying for the invisible thread of trust

How much does it cost to have people trust you? Well, that’s hard to quantify. Except that you do know how psychologically unsafe it feels when there is no trust. One only needs to look at how the US is doing, to see a clear evidence of what happens when there is little trust in the society.

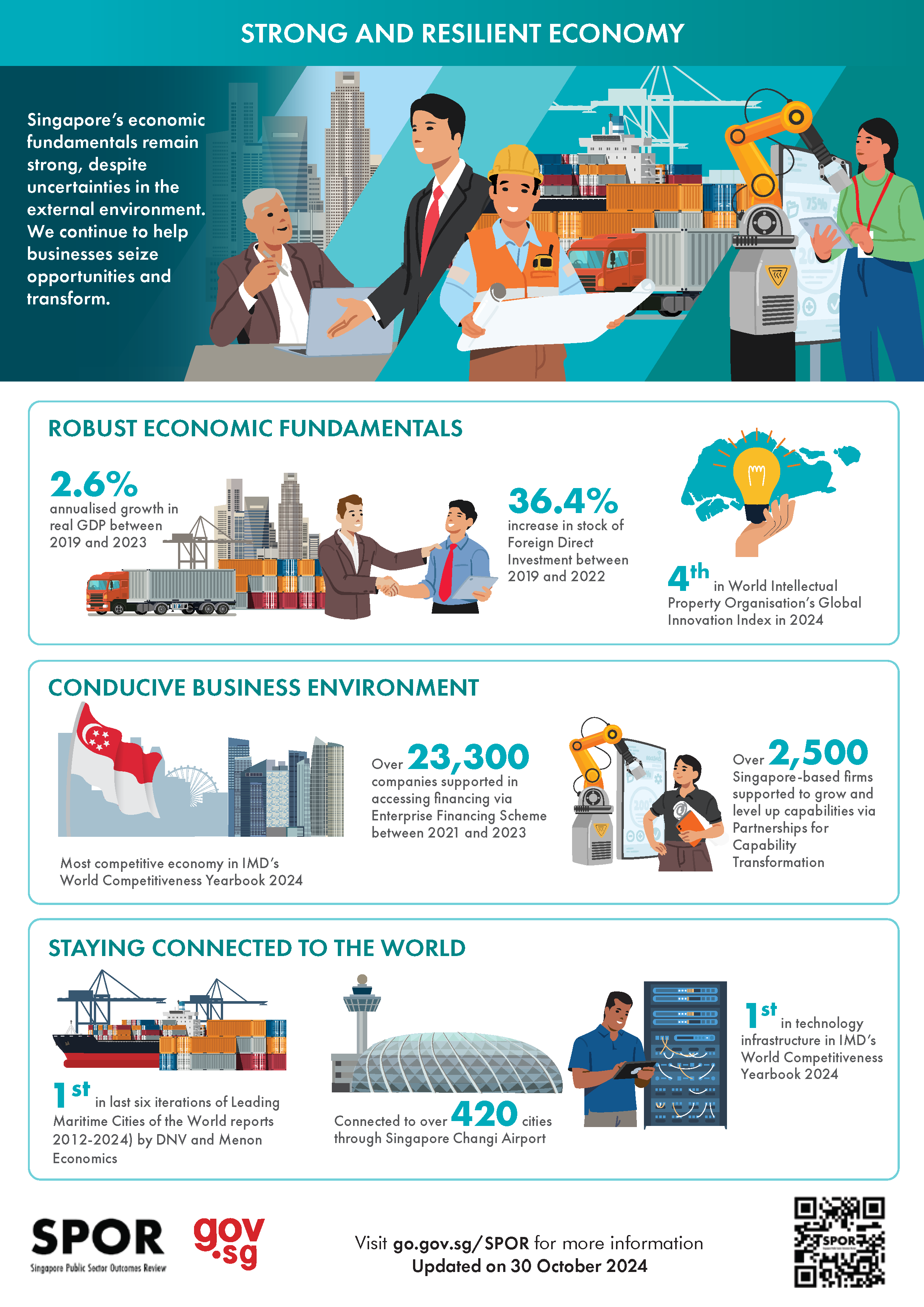

Here in Singapore, the Government has consistently sought to imbue a greater sense of trustworthiness. In most of their actions, they try to signal a clear and upright stance about what they are doing.

For example, one of their key yearly publications is the Singapore Public Sector Outcomes Review.

It shows citizens what the Government is focusing on.

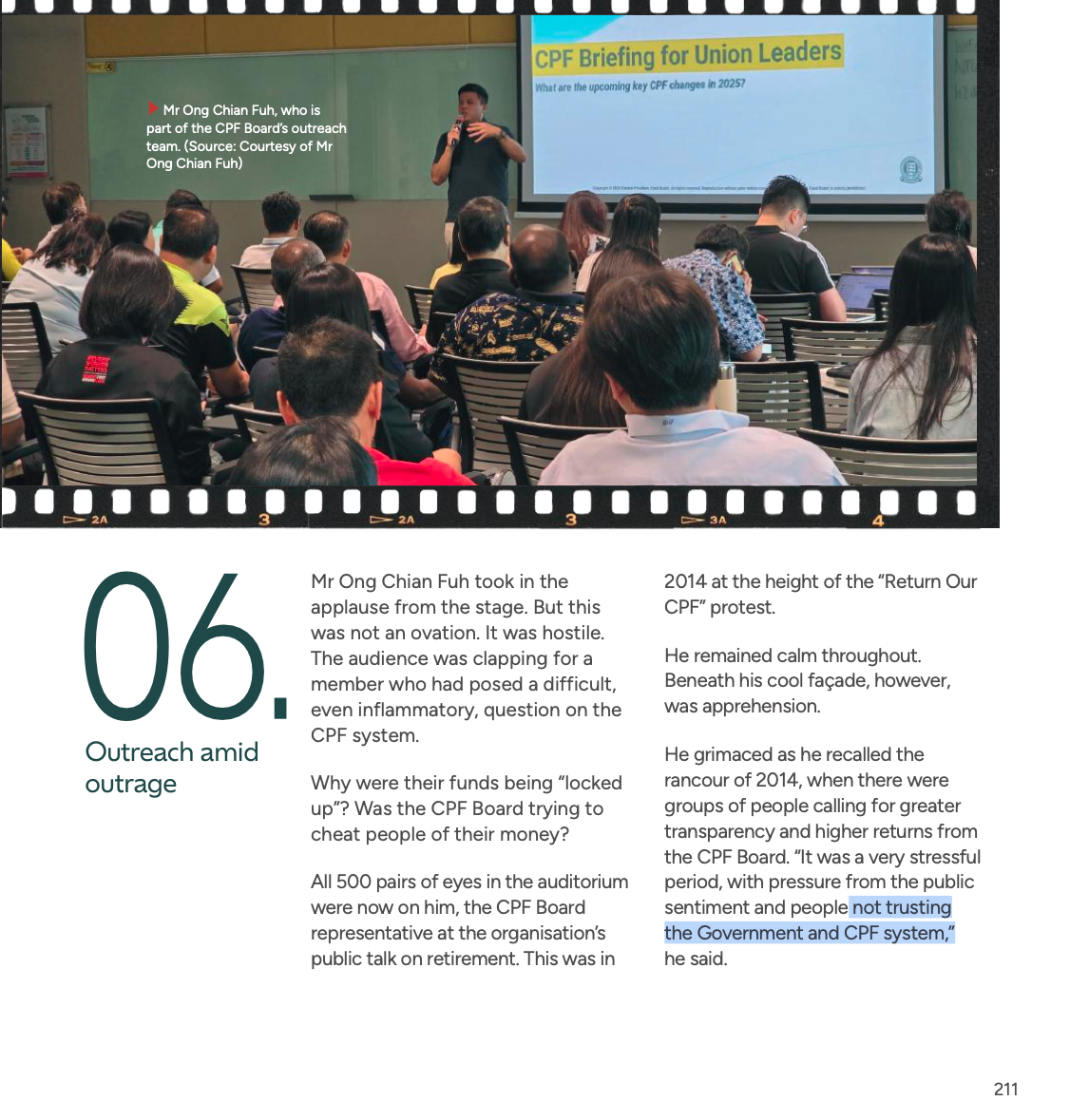

But if you look at other publications from key public institutions such as the Central Provident Fund (CPF), you would also notice how the CPF spent the money to communicate key narratives around trust.

In 2014, there were multiple protests around “Return Our CPF”, as the public began to feel that the CPF was locking away their funds, and not allowing them to access it.

CPF’s 70th Anniversary Book addresses the concerns there, and helps people to now understand that the CPF was designed with Singaporeans at its heart, and without any desire to try and lock it away.

It rebuilt the trust people had towards the CPF system. And it’s why a book, at 198k, might seem cheap.

After all, if you divide it by just a paltry 1000 people who end up reading it, $198 is still a cheap price to pay for trust.

It positions you as the inevitable thought leader

When your story is enshrined through a book, people give you more respect for it. Just look at my own book.

When I first published it in March 2023, I was a 27 year old. I had a grand total of 1 full time job.

In a traditional sense, no one should have given me a stage to speak on. But with that one book, I was given stages in front of universities, shared panels with CEOs on them, and got the chance to do keynotes abroad.

Why?

Because I wrote a book.

Many people still say a book is a waste of time and money, but I would like you here to look at one thing.

How long has the book lasted? In Joan Cummins’ 2006 book, “Indian Paintings before the Creation of the Mughal Atelier”, she talks about how the earliest surviving books came in the 10th Century AD, having come through the Buddhist manuscript tradition.

For thousands of years, the book has still been the main way of codifying knowledge.

Yes, you might say videos, films, photos are also good stores of knowledge, but nothing comes close to the book. It’s the most efficient store of knowledge, and the most easily discoverable. For example, a documentary would need hours to digest. But with a book with a simple Command + Find, you can find what you need.

Here, you might still be wondering what you’re paying for. Well, I will tell you what we did.

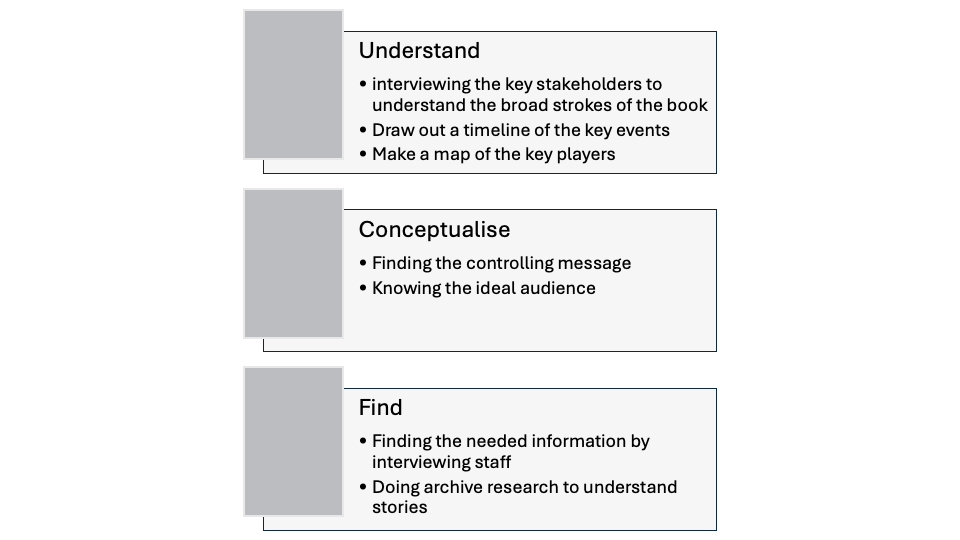

Interviewing the organisation’s key stakeholders to understand the broad strokes of their work

For example, during our work with the shipping agency, we had to first speak to the CEO 3 times, for 2 hours each, to understand where the broad strokes of his organization’s history were.

We then had to write out a timeline of where the key moments in its history were.

After that, we even had to write out a key map of the main players of the story. It was then that we had a clearer idea of who to interview, and for what.

Conceptualising the book

This helped us to conceptualize the book. Now now, conceptualizing sounds like a big word.

What exactly is it?

We define conceptualisation as two things.

Firstly, you need to know the main message of the book. And then you need to know your ideal audiences. Who’s probably going to be the one reading the book?

What would they find helpful?

What would make them toss the book, if they read it?

Jokes aside, you really need to understand your ideal reader. For us, that came through a lot of interpersonal conversations with their staff, their agents, and trying to understand what they were interested in from the CEO.

Following the author and understanding his daily life

To build a good story, we then had to follow the author through his daily life.

We became a fly on the wall.

We sat in on meetings between him and his staff, followed him for his annual conference, and even went to his warehouse in the port to try and better understand the work that he was doing.

We even sat in his Porsche to try and understand a day in the life of a CEO. The power, the fame, and the money involved.

None of that was easy.

And that’s why none of this comes cheap.